by Zainab bint Younus

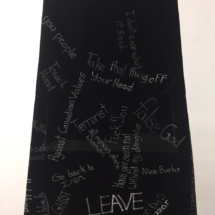

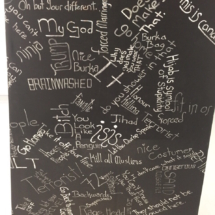

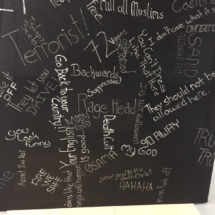

“Take that thing off your head!” “BRAINWASHED.” “Go back to Iran!” “You look like a penguin.”

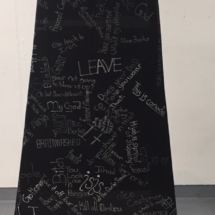

Standing at around 5”8, an obelisk of soft black fabric is covered in silver paint that spells out these words, and so many more – all hurled at Muslim women across North America, often by complete strangers.

“Privilege: Or, Shit People Say to Muslim Women” is a sculpture created by Canadian artist Lindsay Budge – who is also a niqab-wearing Muslim woman. A student at Camosun College in British Columbia, Canada, she’s had her fair share of less than pleasant comments and encounters with strangers who have felt perfectly at ease uttering sentiments of anger, disgust, and hate towards her simply due to her attire.

In a post-9/11, post-Iraq, post-ISIS world, political rhetoric and international policy have impacted one group of people more than any other: Muslim women. Whether in the East where their homes and their lives are devastated by war crimes and American drones kill 90% more civilians than military opponents; or in the West where they have been born and raised and yet are treated as unwelcome foreigners and physically assaulted because of their faith, Muslim women are – across the board – the demographic most vulnerable to violence of all kinds.

Despite the statistics, most people are oblivious to the painful realities that Muslim women must deal with on a daily basis. The idea that “all Canadians are polite” and “Canadians aren’t racist” is a pleasant one, but an unfortunate fiction when one pauses to take a look at our nation’s history and statistics. For people like Ms. Budge and the many, many women whose experiences she represented in her project, there is nothing about those statistics that is impersonal. “Hate speech” is not a KKK manifesto published online, but something heard in the streets, at the mall, in the bathroom of a college, standing in line at the grocery store or walking to the beach with children in tow.

Writer Zainab bint Younus spoke to the artist about the inspiration and meaning behind her piece.

Ms. Budge, what inspired you to create this sculpture? Can you explain what it means to you and in particular, why you entitled it “Privilege”?

Originally, I was given an assignment for my 3D sculpture class, which required us to create a freestanding sculpture that acted as a metaphor for the human body, depicting concern or authentic experience.

What originally came to mind was one of those cut out photo stands, where there is some kind of character and you stick your head into the cutout, but with hate speech instead of a cartoon character.

It was the ‘experience’ part of the assignment that got to me. Muslim women who cover tend to have things said to them often on the street, so muc so that we tend to normalize it. And when we explain what happens, it tends to be dismissed as not that big of a deal, or an overreaction. I wanted it to be visible, in a way that would be very clear and impossible to ignore. However, I scrapped the cut out part of my idea and instead chose fabric – abayah fabric, to be precise, as a symbol of the specific type of clothing that elicits these reactions.

As for the name, it struck me at the end when I realized how much more hate speech I kept adding to the fabric. People say these things because they feel privileged enough to get away with it – they feel safe to say these hateful things to Muslim women because they know that there will be little or no consequences to doing so.

What do you think are the causes behind the verbal abuse that you and other Muslim women have faced?

Oh, there are so many reasons! For some people, it’s xenophobia; for others, it is bottled up anger regarding their own life situations, whether socio-economic or otherwise – so people feel like lashing out at others, whom they might perceive as the reason that they are not doing well. There has also been a lot of negative media and propaganda pushing the “Us vs Them” mentality since the Bush era.

Muslim women who cover are easy to identify, and there is this idea that we are oppressed, and do not talk for ourselves, so it’s easy for people to pick on those whom they perceive as weaker. Hate goes in waves throughout history, and right now it is Muslims who are in the path of the wave.

What do you hope to accomplish with your project? What effect do you want it to have on viewers?

I just want people to be able to visualize what they are told is happening – we know that hate crimes, against visibly Muslim women and people of colour and faith who are perceived to be Muslim (even if they’re actually Sikh! Or lupus patients!) – but a lot of times, people don’t get it until they see it.

I want there to be a realization of what is said to us. I also left space on the fabric to show that there are always new things being said – so more room to include those. Some of the words on the fabric are also faded, to symbolize words that were said in the past, but the effects of which remain.

I had a lot more words to add, and some were hidden as the fabric was attached to the frame, but I think that overall it worked out well. It should also be noted that all the words and phrases that are shown were spoken by adults – when a child calls you a ninja, it doesn’t have the same negative effect, especially since most kids tend to think ninjas are pretty cool!