When did addiction start and is it a problem that is still increasing? To answer that fully, we need to look back four hundred years or so. But yes, addiction is very much a problem on the increase.

Though drugs and alcohol are as old as history itself, a significant moment occurred in Britain in the early 17th century.

The age of innocence

The year 1604 saw publication in London of the play ‘Othello’, a tragedy by William Shakespeare which contains the first instance of the written word ‘addiction’ in English (Othello Act 1, Scene 1). Perhaps this word just hadn’t been needed before. Or maybe Shakespeare himself had a few concerns because after all, clay pipes containing marijuana were recently dug up in the garden of his house(2). But he wasn’t the only person in Town with addiction in mind.

In the very same year, a treatise entitled ‘A Counterblaste To Tobacco’(3) was published by the recently arrived Scottish, and now English, King ( James VI and I). It is an early example of the vast canon of anti-smoking literature that continues to appear even to this day.

Year 1604 perhaps marks the end of the age of innocence – the time when drink and drugs were expected to be innocent fun. Both of these men would no doubt be shocked to see how addiction of all kinds has mushroomed in the four hundred or so years since they set the hare running. Because run it certainly did.

The age of consumption

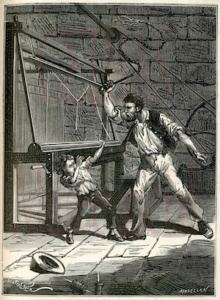

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were characterised by mass production of alcoholic spirits such as Gin(Britain), Absinthe(France) and Rum(the Americas) which at times seemed to threaten social breakdown on a massive scale. The squalor and degradation of Gin Lane was a very real sight in many towns. In these centuries too were seen widespread use of tobacco, huge importation of sugar and large-scale gambling (Tulip Mania(4) in Holland in 1637 and the South Sea Bubble(5) of 1720).

The age of exploitation

The age of exploitation

In the nineteenth century people carried on in the same vein as before but added in a few exciting substances as well, especially opium, cocaine and cannabis. These were all previously known but now became widely used in more socially acceptable form. Opium (as laudanum), cocaine (in medicines, tonics and sodas such as early coca-cola) and cannabis (often smoked in ‘hashish clubs’(6)). People and corporations were starting to make big money from the addiction of others. The British government cornered the Chinese opium market, making millions(7).

The age of consequences

The twentieth century saw the first attempts to control the problem, notably the Prohibition era in the USA. With regulation came criminal activity and gang warfare. At the same time, people began to turn to other substances such as prescription drugs and designer drugs. Increasingly too, the later decades saw a big rise in behavioural addictions – gambling, pornography, eating disorders and shopping being the most obvious. People were waking up to the extremely negative consequences that follow such behaviour but that didn’t deter them – they just wanted more. Addiction was now getting a really bad name.

The age of manipulation

The twenty-first century has been characterised by the dark arts of manipulation. Everyone is at it – governments, corporations and individuals are bidding to achieve, mainly through social media, a mastery over our hearts, minds and actions. This dwarfs the control and subjugation of the masses that kings, dictators and warlords achieved in former times. It was The Buddha who first identified ‘desire’ – for material things, respect or power for example, as the source of human unhappiness. The hidden persuaders of the internet (and the dark net too) exploit this to the full. And where there is human unhappiness there is often substance abuse and addictive behaviour. We see examples everywhere. A global online casino may target teenagers playing video games and lead them from gaming into gambling; a social media platform such as Twitter or Instagram may be employed to apply peer pressure on individuals to use drugs or indulge in other addictive behaviours; the desire for Facebook ‘likes’ may drive youngsters into excessive dieting or grotesque exercise routines.

Addiction is sometimes described as an attachment disorder – Hamlet would have known what that meant. Certainly, many addicted people have difficulties around feelings of love and abandonment and are simply not good at relationships. Such people are easy to manipulate as they wander through the dangerous media jungle because they are looking for things that are easy to obtain and attach to – Facebook likes, chat rooms, online gaming communities meet that description. Drugs too.

Shakespeare may not have given much thought to the little word that he, for the first time, committed to writing in 1604. Today, if you put that same word into Google or a similar global search engine, you will get over one hundred thousand hits per month.

So, yes…..

…Addiction is alive and well and it is growing.

Fast.

Great article. Important history.

But what is ‘attachment disorder’?

Thanks for your comment. Attachment disorder is a recognised condition affecting mood and behaviour that usually begins in childhood. Sufferers find it hard to establish meaningful relationships especially with primary care givers such as parents. such people tend to find it easier to attach to mood altering substances and behaviours because of the illusion of support and control that these provide.

Hi Rupert. From the moment we are conceived, we start ‘to attach’ to our mothers. Upon birth this starts to widen out to fathers and other care givers. Its this attachment or love and care that helps us grow into well rounded adults. Take this away, and serious problems arise. John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth were the first to scientifically test this theory. Psychologists call this ‘Attachment Theory’ and both the Diagnostics and Statistical Manual (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) list a considerable amount of illnesses, both physical and mental, that can come from a lack of basic human affection and care. I hope this added a little to Chris’ explanation. All the best